Less can be more: End of the road for private cars?

With dwindling sales and a staggering failure to respond to emissions pressures, are we seeing the beginning of a new era in our relationship with motor vehicles?

Well, probably not. At Environment Journal we clearly advocate for the least environmentally damaging solution to any problem. Like mobility, for example. As a UK publication we also fully understand the limitations of alternatives, a country that has neglected its existing public transport responsibilities to such an extent 90% of council-run bus services have vanished in the past two decades alone.

Meanwhile, widespread lack of investment in improvements and upgrades means the idea of modernisation now sends the country into the throes of budgetary panic. What price not starting to spend on high speed rail when the technology was first on our doorstep.

And, when it comes to active modalities – walking, wheeling or cycling – provision is no better. And the disruption now being caused in order to introduce bicycle paths and pedestrian walkways en masse is the source of much furore, not to mention a few conspiracy theories.

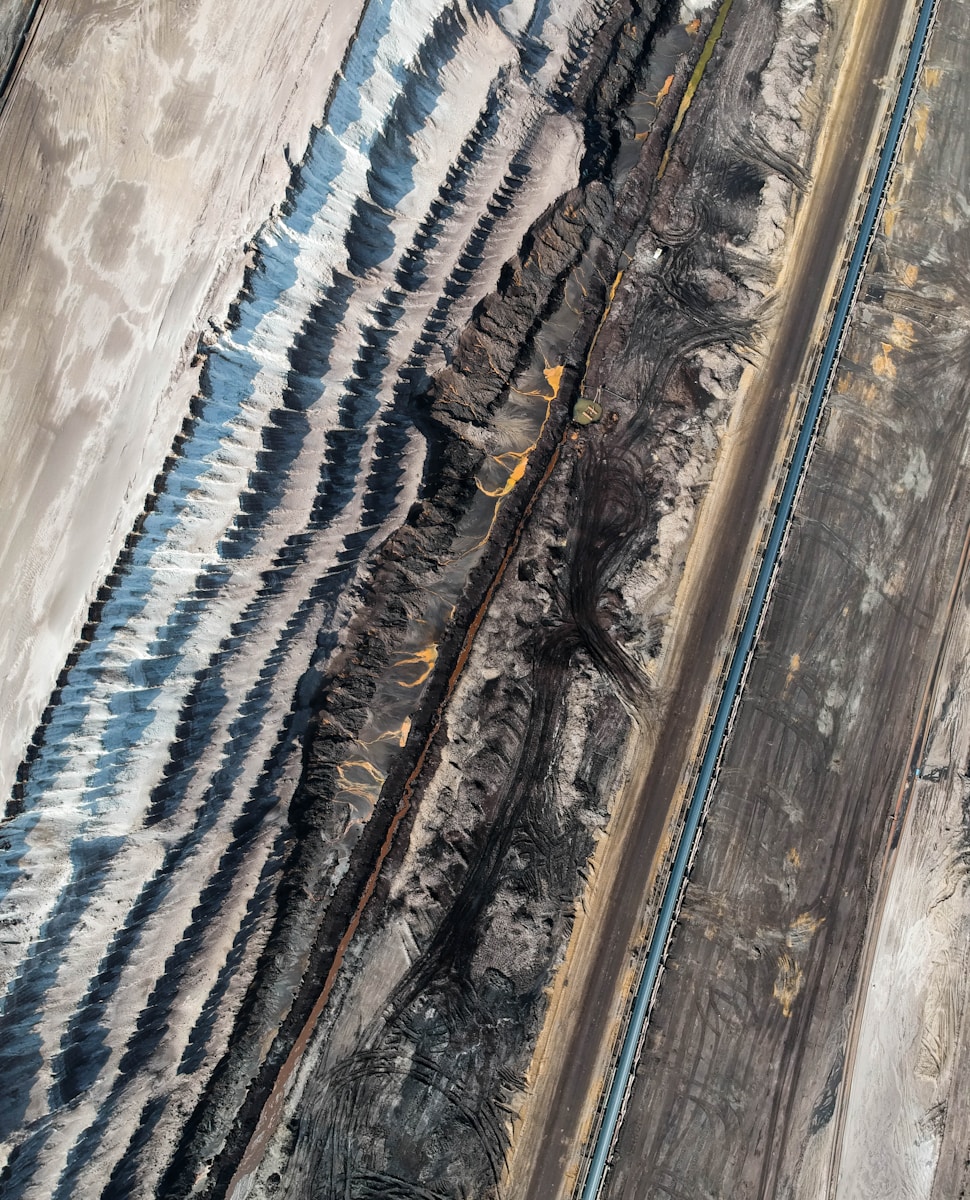

Electric vehicles [EVs] were, of course, never the silver bullet. While it has been shown that lifetime footprint, including the mining of rare earth materials for batteries, is substantially lower for electric than internal combustion engine equivalents (even extracting minerals like lithium requires less physical mining than oil and gas), the focus on plug-in vehicles still ignores several issues.

It’s not just tailpipe emissions our sister publication, Air Quality News, regularly reports on – all moving things with wheels emit particulate matter from friction alone. And as our roads buckle under sheer volume of traffic, simply getting rid of older, higher polluting models and buying new ‘green’ cars will do nothing to free up more free time.

Of course, the issues get far worse. The EV charge network is one of the most regularly covered net zero and emission-related topics on our pages. The UK is so far behind were it needs to be on roll out of technologies 34% of local authorities have no plan on how this will actually happen in practice. By 2030, there’s supposed to 300,000 charge points nationwide. Britain currently has 60,000 or so, and it has taken decades to get to that point. Coverage is also incredibly patchy – so there’s a long way to go.

Recent news the entire Supercharger team at Tesla has been made redundant is a great cause for concern, then. Contracts were just signed with North America’s leading automobile manufacturers, allowing their vehicles access to the now-standardised North American Charging System [NACS]. Ford and GM, among others, are buying into one of the world’s biggest charge point networks, in turn making Tesla eligible for government subsidies.

The US is, amazingly, even further off target than Britain in terms of EV infrastructure. Washington wants 1million by 2030, but right now the country has just 150,000, give or take. It will also need a better spread to reach its goals, with current locations matching population distribution, leaving big questions over the capacity to drive longer distances through rural areas. It’s not clear what Tesla’s cuts will do to all this, and it’s unlikely to mean an end to the Supercharger network. But, at a time when uncertainty over plug-in cars is high, this can only mean more confusion and delays across supply chains and public adoption.

Unsurprisingly, the European Union is faring better with its switch to lower emission vehicles. Already home to the most comprehensive and reliable train network on the planet, and known for high levels of investment in public transportation within and around major urban centres, even the nascent hydrogen transport sector has a clear strategy in the bloc.

A ‘superhighway‘ of hydrogen refuelling stations is in development, aimed at tackling carbon output from road haulage. This is well ahead of the game. Nevertheless, despite having more charge points per person on average than the UK and America, between 2017 and 2023 EU EV sales grew three times faster than charge point installations. To reach 2030 targets, this will need to increase installation of infrastructure by a factor of 10, year-on-year, until the end of the decade.

All of which raises one glaring question – is the EV dream even possible, and will it lead to a fit for purpose future? Studies show many of our greatest net zero and low emission hopes are founded on resources which exist in parts of the world most susceptible to climate change. And the risk posed by extreme weather is going to rise significantly in the coming decades. Meanwhile, the idea of basing a ‘new age’ on the same principles as before, just with a different drive system that needs different metals, is similarly alarming.

We will still be doing untold damage to the Earth through mining practices, decimating natural habitats just as biodiversity is finally getting a look-in. So maybe the answer is moving away from cars altogether – the idea of which is likely to have many reaching for whatever weapon is closest to hand.

But it has been a stark week for motors in general. Following Tesla’s redundancies, we heard that Volkswagen, Mercedes and Stellantis had lost a combined $13billion in market valuation. Order books are down, in some cases by up to 12% year-on-year.

Much of this is being driven by increasing competition from cheaper brands, with the Chinese EV industry considered to be a particular threat in both Europe and the US. The European Commission is even probing into anti-competitive practices, but a tariff of around 50% on EV imports from outside the EU would now be needed to level the playing field again for brands like VW and BMW. That’s unlikely to happen.

This only paints half a picture, too. In Europe, sales of EVs have been slowing overall, and even richer states like Germany have seen big falls – new registrations for plug-ins declined by 28% in the year to March 2024. In Norway, they were down 50%.

In the UK, EV demand among private drivers has plummeted by around 25% since last spring, and while fleet operators are making up some shortfall, in February year-on-year sales for all car types, including internal combustion engines, were down by 2.6%. For the EU, sales had fallen by 5.2% in roughly the same period (12 months to March 2024). With deadlines now fast approaching for an end to the sale of new fossil fuel motors, this trend is likely to continue.

Serious economic challenges continue to plague the same Western countries in which car sales are slipping, too. There’s not enough money to get transport to where we need it to be, and that counts for drivers as much as authorities responsible for rolling out infrastructure, and companies based in these regions that design all this kit.

Cost of living, wage stagnation, and multiple housing crises are affecting vast swathes of the population in Europe and North America. Meanwhile, another product of urbanisation – rampant congestion – means many are choosing not to own a car for practical reasons, even if they could afford to run one. Hence the boom in car clubs we have reported on recently. The future of the industry as we know it has never looked so uncertain, then, although we’re sure a smooth bounce back to ‘business as usual’ is likely to prove a pipe dream. Although, if electronic music composer-legend Jean-Michel Jarre can become the first passenger in history to ride in a flying car, maybe anything is possible.

More features and opinion:

Quick question: How is the North West leading England’s hydrogen revolution?