Cloud-based computing and AI are continuing to drive greater energy demands at server hubs. But the latest generation not only cut power usage, they can help manage and balance wider grid supply, and contribute to renewable energy surplus.

In 1965 Gordon Moore theorised advancements in information technology were happening at such a lightning pace computer processing capabilities would double every 18 months. Later revising this to every two years, the concept rang true throughout the second half of the 20th Century. Today the timeline is changing, and Moore’s Law is widely considered to be outdated.

Nevertheless, digital technology continues to develop apace, and as a result our need to store more and more zettabytes of data is growing in tandem. Putting this into context, according to data operations specialist Rivery.io, 90% of the 64ZB of digitised information in the world by 2023 had been created during the preceding two years. Between now and 2025, this is set to more than double, hitting a projected 180ZB.

Data centres, those massive buildings or groups of buildings used to house computer storage systems, are already commonplace, but their numbers will need to grow significantly to cope with future needs. By 2022, they already accounted for a combined 3% of global electricity use, and this excludes energy needed to power cryptocurrency mining. That’s an awful lot of wattage at a time when organisations and members of the public are being asked to cut down on how much they use in a bid to contribute towards climate action. But what if data centres themselves could also make a positive contrition to our transition to greener ways of working and living?

‘There’s a huge way to go before that,’ says Jonathan Anstey. As Sustainability Director at True, a company helping businesses reconcile energy costs and sustainability, he’s certainly well-placed to comment. “I personally think, and this is not an uncommon opinion, we are on the foot of the hill with artificial intelligence (AI) and the computing power and server space that will be required over the next decade is going to be huge. So the scale of the problem of data centres and environmental impact is only going to get bigger.’

Alarmingly, though, this huge drain on resources is far from common knowledge. As our sister publication, Air Quality News, reported on in 2022, the footprint of technology is often something organisations, and their decision makers, are painfully unaware of. We ask Anstley if he feels knowledge of this is beginning to increase, and whether he feels there is a growing understanding of the need to make data storage less of a resource black hole.

‘I would probably say within most organisations the level of understanding is about the same as the average man or woman on the street. So limited, because it is relatively unseen. It’s not something we tend to look at day-to-day when considering emissions, net zero strategies, carbon reporting,’ he replies. ‘Most organisations would just see greenhouse gas from data centres as scope one or two emissions for the company running the data centre — so out of their hands, not their responsibility. A lot of people wouldn’t go on the record as saying this, but I often hear it said that ‘my scope three emissions’, so those tied to supply chains and partners, not direct energy use or on-site output — ‘are someone else’s scope one’.

‘I think the biggest driver for change will be continued improvement for customers. So the buyers of services, like data storage, will be demanding better carbon credentials from their suppliers. We’re starting to see this in food and drink distribution. So lots of True’s customers would say ‘we have to have this running on green energy, because our customers, for example the big supermarkets, are applying pressure from their end’. This absolutely applies to data centres. Probably more so, with these big tech behemoths like Amazon Web Services, Google and Microsoft demanding data centres meet certain standards.’

Running on renewable electricity is certainly a big step in the right direction, and things are moving fast. Last year, Forbes published an advertorial on how data centres were driving the renewable energy transition in itself. That’s a bold claim, but it also makes sense. A rapidly growing sector that needs more and more power at a time when governments, local authorities and the energy industry are spending billions on switching away from fossil fuels. Estimates and calculations for demand, and how many wind farms or solar sites need to be created to meet that, includes the needs of data centres. The greater that is, the higher the chance of more renewable facilities being commissioned.

‘PPAs (power purchase agreements) mean two parties have agreed to buy and sell power. So you have a renewables developer that will go out with a large multinational investment and build offshore wind farms, or huge solar farms. They will be generating a huge amount of clean energy each year, and they then seek a buyer for that quantity on an annal basis to make the project viable,’ says Anstey. ‘I think data centres are making this type of contract more commonplace, and a lot of organisations are now looking at this approach because it’s very marketable. It’s visual. The additionally is clear – ‘as a direct result of placing our business electricity supply with this developer, we have caused a wind farm to be built’. That’s good PR.

‘To chuck another acronym in there, direct server return (DSR) is also a big trend in data centres, so load shifting… Data centres need a guaranteed up-time of 99.999% of their lifespan. This is often referred to as The Five Nines. So they’re online every second, essentially. To achieve that, they need backup power in case of a blackout. Up to today, that’s typically been diesel generators on the roof… What we’re starting to see now is new data centres being built and existing ones transitioning away from diesel, and switching to battery storage,’ he continues. ‘Then that battery asset on the roof is being used to load shift and take the centre off grid at times when the grid is under stress. And when it’s sat there, in the 99.999% of time it’s not being used, it can be used to export power back to the grid and smooth some of that wider fluctuation we have in demand.’

It’s certainly a marked difference to the traditional model, essentially turning data centres into mini power sources that can help alleviate pressure on national grids. And these facilities are also being used in response to demand for heat. A data campus — large scale data centres — can produce up to 300MW 0f heat, which is roughly enough to power a small-sized city. Increasingly, we are seeing plans for data centres in locations where new developments are taking place, for example a suburban housing estate, with heat from the facility sent to a localised pipe network, turning waste energy into central heating. Elsewhere, Exmouth Leisure Centre in Devon has been keeping its pool at a temperature of 30C 60% of the time since last year thanks to warmth from data storage.

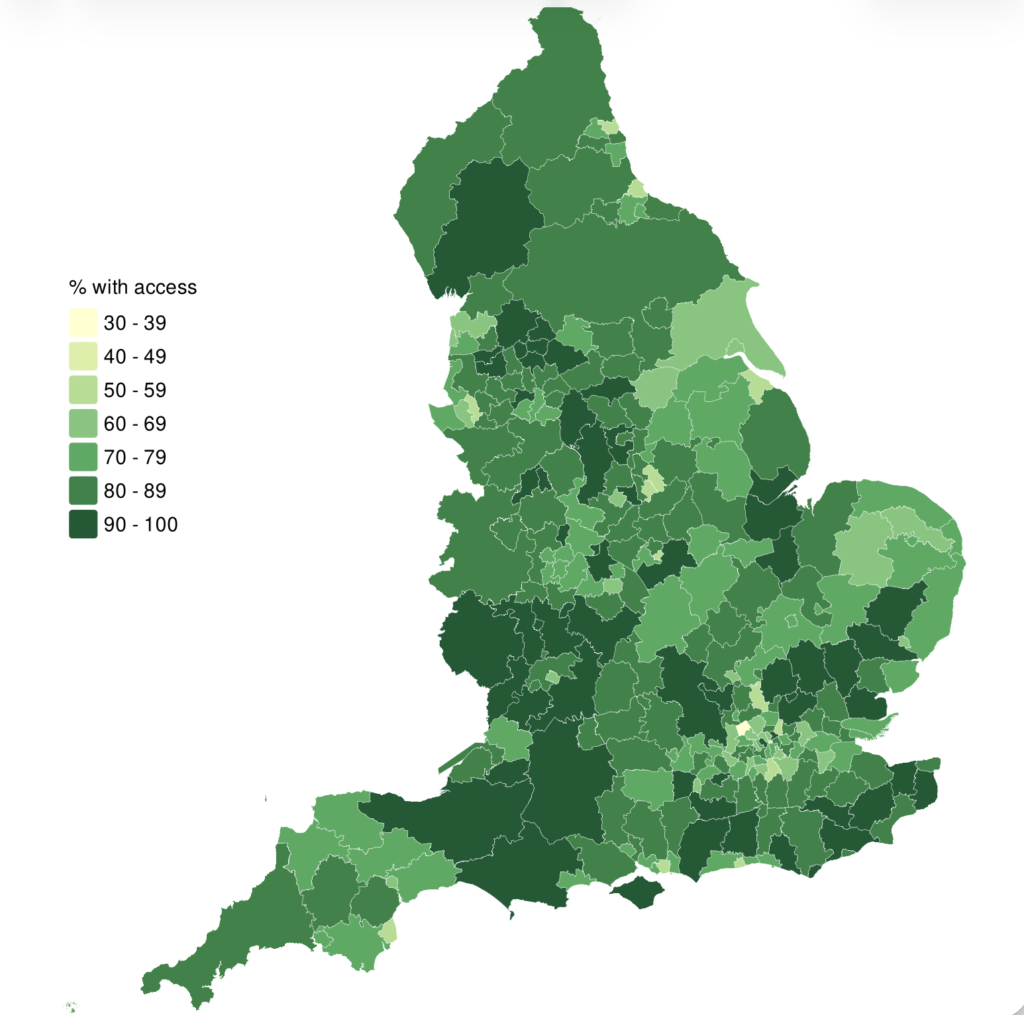

‘The siting of data centres is now another big thing. More and more are being built and a big consideration for their operators is where they are. Because they use huge amounts of energy there needs to be the ability to plug-in to a physical grid connection, so being close to potential sources of renewable energy or other sources of energy is important,’ says Anstey. ‘One example is using a waste-to-energy solution, with data centres built alongside waste processing plants, and that waste being converted to energy, whether that’s through biomass or incineration.’

More features:

Cybersecurity lessons from Leicester City Council, MP and Electoral Commission attacks

Opinion: Where do smart buildings fit into the net zero conversation?