Following news that 2025 was the third hottest year on record, beaten only by 2023 and 2024, new British research suggests even with more downpours farmland is likely to fail.

Conducted by scientists at the University of Reading, the study focused on the impact of climate change on soil moisture during growing seasons. This is when nature’s demand for water is highest, with warmer temperatures leading to soil drying out faster and rainfall unable to keep pace.

The team published their peer-reviewed research in the journal Nature Geoscience on Wednesday, and identified the regions most at risk of continued agricultural droughts. Western Europe, including the UK, Central Europe, the Pacific coast of North America, northern South American countries, and Southern Africa were labelled as ‘hotspots’.

In comparison to previous studies on similar phenomena, the Reading analysis did not concentrate on precipitation patterns or yearly soil moisture averages. Instead, it honed in on the most resource-heavy months for crops.

The findings show that moisture levels at the beginning of growing season determine summer drought risk, so even if rainfall increases as the weeks pass by, warmer temperatures will speed evaporation up and leave land vulnerable to drought as summer arrives. Lower emission climate pathways would reduce the severity of this, but the risk would still be evidence.

‘Climate change is heating the air, which makes more water evaporate from soil and plants. This dries out fields even when more rain falls, especially during spring in Europe and North America,’ said lead author Professor Emily Black, of the University of Reading. ‘As the planet continues to warm, agricultural droughts could become much more common this century in regions that grow much of the world’s food. Farmers will need crops that can survive drought and better ways to manage water supplies.’

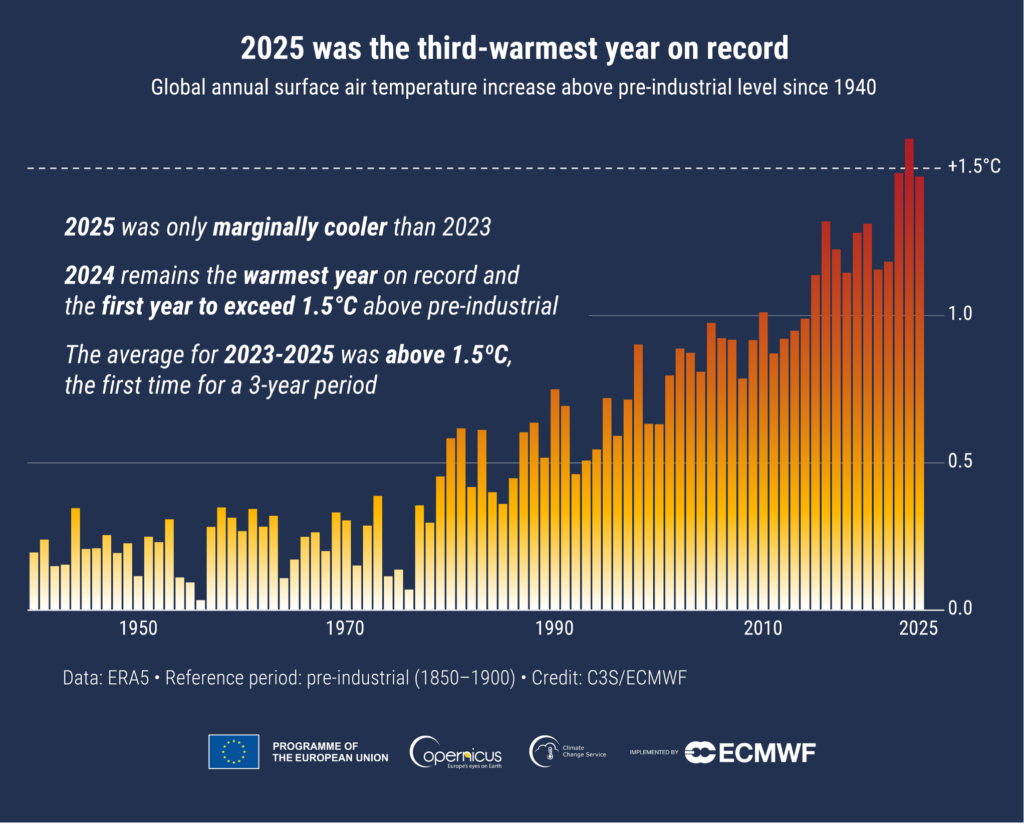

Arriving at the same time as the study, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, which operates the European Commission’s Copernicus Climate Change Service and Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, confirmed that 2025 was the third hottest year on record. Average temperatures were 1.52C above pre-industrial levels. Only 2023 and 2024 were warmer, meaning the last three years have consecutively breached the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

‘Copernicus was established to provide policymakers, businesses, academics, and citizens in Europe and across the world with trusted, independent climate and atmospheric insights to inform decisions,’ said Mauro Facchini, Head of Earth Observation at the Directorate General for Defence Industry and Space, European Commission.

‘Today’s results show just how vital that mission has become,’ he continued. ‘Exceeding a three-year average of 1.5C above pre-industrial levels is a milestone none of us wished to reach, yet it reinforces the importance of Europe’s leadership in climate monitoring to inform both mitigation and adaptation. We expect Copernicus to play an important role in implementing tailored new tools for European climate resilience and risk management.’

(C) Copernicus

Top image: Zhiyuan Sun / Unsplash

More Biodiversity, Climate Change, Nature & Sustainability: